Prostate Cancer

Overview

What is Prostate Cancer?

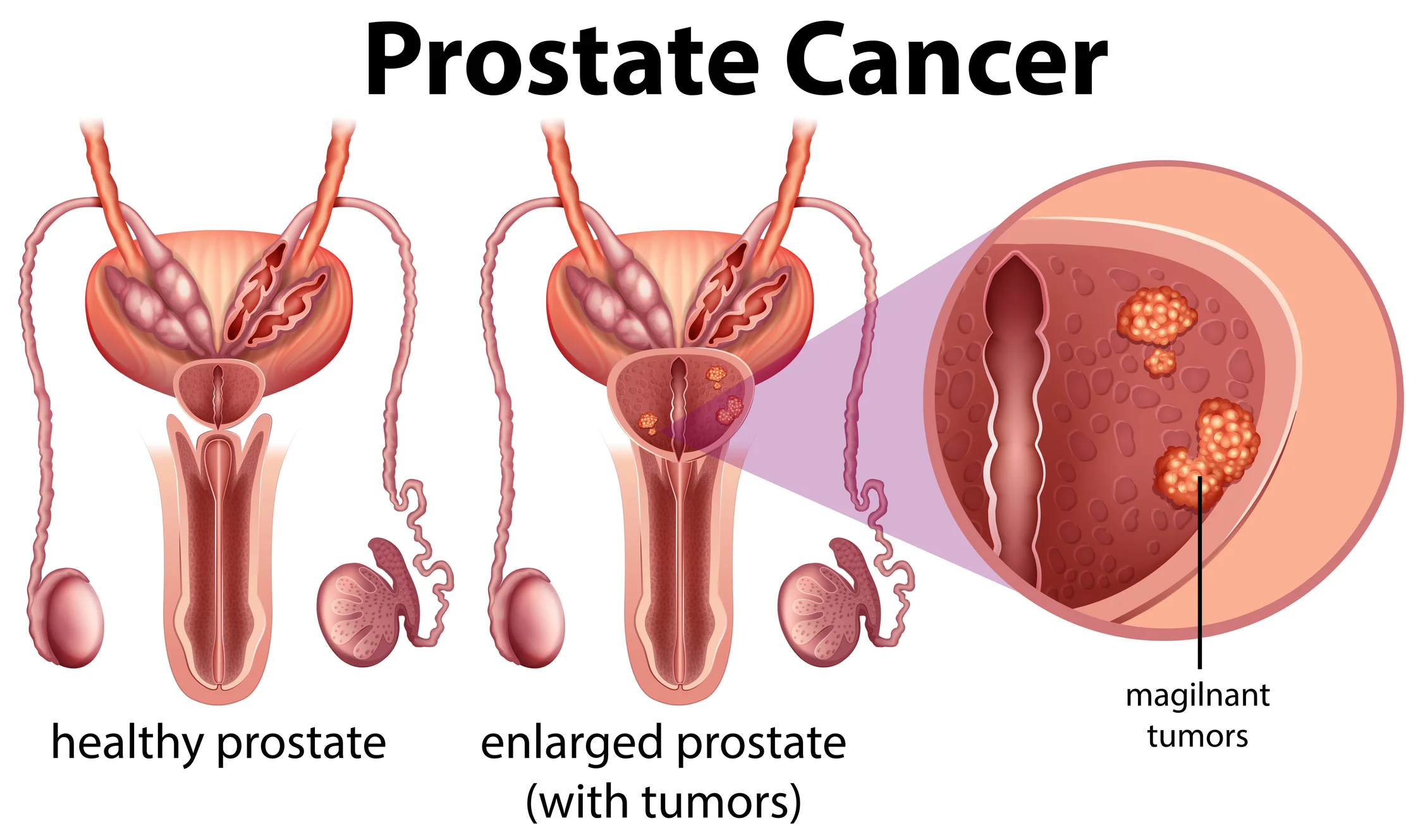

Prostate cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancerous) cells form in the tissues of the prostate. The prostate is a walnut-sized gland in the male reproductive system that sits below the bladder and in front of the rectum. It surrounds part of the urethra (the tube that empties urine from the bladder). Two smaller pairs of glands, known as seminal vesicles, are attached to the back of the prostate. The main role of the prostate and seminal vesicles is to make fluid for semen.

Types of Prostate Cancers

Prostate cancer can be grouped according to the type of cell that the cancer started from. The most common form of prostate cancer is adenocarcinoma, which arises from the gland cells in the prostate that are responsible for making fluid for semen. Adenocarcinomas make up more than 95% of primary prostate cancers1. Rare tumours such as small cell carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumours and sarcomas account for the remaining cases.

Many prostate cancers are confined to the prostate and grow slowly without causing serious harm. However, other types can be aggressive and spread quickly.

How Common is Prostate Cancer?

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in men in Singapore. The number of cases has grown steadily over the past fifty years, due in part to the ageing population and the introduction of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing (a blood test that measures the level of PSA which is high in prostate cancer)2. The good news is that despite the higher numbers, prostate cancer accounts for comparatively fewer deaths among all cancers.

It is believed that as many as 80% of men who reach the age of 80 will have prostate cancer3. As most cases are slow growing and do not show symptoms, many men are likely to die of other ailments of old age without ever realising that they have prostate cancer.

Causes & Symptoms

What causes Prostate Cancer?

Prostate cancer happens when cells in the prostate develop changes (mutations) in their DNA that cause the prostate cells to grow abnormally and develop into a tumour. The exact trigger for the mutations is not fully known.

Prostate Cancer Risk Factors

Doctors may not always have an explanation as to why one person develops prostate cancer, and another does not. However, there are certain risk factors that increase the likelihood of a person developing prostate cancer, including4:

- Age: Your risk of prostate cancer increases as you age. About 65% of prostate cancer diagnoses occur in people older than 65 years3.

- Race: For reasons that remain unclear, Black people have a greater risk of prostate cancer compared to people of other races. They also tend to have more aggressive or advanced forms of prostate cancers.

- Family history: If a blood relative, such as a grandfather, father, uncle or brother, has been diagnosed with prostate cancer, your risk may be increased two- to three-fold5. The risk is even higher for men with several affected relatives, particularly if their relatives were young when the cancer was diagnosed6. In addition, a family history of genes that increase the risk of breast cancer (BRCA1 or BRCA2) or a very strong family history of breast cancer can also increase your risk of developing prostate cancer4.

- Obesity: The actual relationship between obesity and risk for prostate cancer is somewhat unclear, with research in this area showing mixed results. However, what is known is that obese patients tend to have more aggressive forms of prostate cancer that are also more likely to return after initial treatment4.

Having one or more risk factors does not mean that you will get the disease. Many people with risk factors never get cancer, whilst some with no known risk factors do.

What are the Signs and Symptoms of Prostate Cancer?

Prostate cancer often shows no symptoms and is more likely to be picked up on screening tests before symptoms develop. Prostate cancer that is more advanced may cause signs and symptoms including4,7:

- Trouble urinating - difficulty starting the flow of urine, trouble emptying the bladder completely, weak or interrupted ("stop-and-go") flow of urine, frequent urination (especially at night)

- Blood in the urine

- Blood in the semen

- Bone pain - often felt around the pelvis, back and hips

- Unintentional weight loss

- Erectile dysfunction (Trouble getting an erection)

Other prostate conditions may cause the same symptoms. As men age, the prostate may grow bigger and block the urethra or bladder which may cause trouble with urination or sexual problems. Speak to your doctor if you are experiencing persistent symptoms to have them further investigated.

Diagnosis & Assessment

Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer

If prostate cancer is suspected based on results of screening tests or symptoms, your doctor will investigate further to determine if you have cancer4,7:

- Physical examination: This would include a digital rectal examination, which is a bedside procedure where your doctor inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into your rectum to feel the prostate gland for any abnormal areas.

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level: PSA is a protein that is produced in small amounts by normal prostate cells, but in greater amounts by prostate cancer cells. The chance of having prostate cancer rises as the PSA level goes up, but there is no set cut-off level that can accurately determine the presence or absence of prostate cancer8. Once prostate cancer is diagnosed, the PSA level can be used together with digital rectal examination findings and tumour grade (determined on the biopsy, described below) to help decide if further tests (such as CT scans or bone scans) are needed. Repeated testing of PSA levels during and after prostate cancer treatment is useful as an indicator of how well treatment is working, and in watching for a possible recurrence of the cancer after treatment.

- Prostate biopsy: Your doctor may recommend a procedure to collect a sample of cells (biopsy) from your prostate to diagnose prostate cancer. A transrectal biopsy is the removal of a tissue sample from the prostate by inserting a thin needle through the rectum and into the prostate. This procedure is usually done with ultrasound or MRI to help guide the needle into the tumour. The sample is then analysed in a laboratory to determine whether cancer cells are present.

- Transrectal ultrasound: Ultrasound uses sound waves to visualise the prostate gland. This is most often used during a biopsy to guide the needle into the part of the prostate gland where the tumour is suspected.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): In some situations, your doctor may recommend an MRI scan to create a more detailed picture of the prostate and surrounding structures.

How is Prostate Cancer Assessed?

After prostate cancer has been diagnosed, you may undergo further testing to determine the extent (stage) of the disease. Prostate cancer spreads most often to bones or other lymph nodes outside of the pelvis. It is less likely to spread to the liver or other organs. Tests that you may have include:

- Staging tests: Staging, usually done with bone scan, PSMA-PET scan, PET-CT scan or MRI, is done to find out whether the cancer has spread, and if so, to what parts of the body. In prostate cancer, staging tests may not be done unless there are symptoms or signs that the cancer has spread, such as bone pain, a high PSA level, or a high Gleason score (described further below)7.

- Genomic testing: Genomic testing analyses your prostate cancer cells to determine if there are specific gene mutations (changes) present. The results may help to determine how quickly the cancer is likely to grow and spread. Genomic tests are not necessary for every person with prostate cancer, but they might provide more information for making treatment decisions in certain situations.

Prostate cancer is graded according to the Gleason system, which describes how abnormal the cancer cells look under the microscope (ranging from Grade 1 with cells that look similar to normal prostate cells, to Grade 5 with very abnormal cancer cells) and how likely it is to spread8. Since prostate cancers often have areas with different grades, a grade is assigned to the 2 areas that make up most of the cancer. These 2 grades are added together to yield a Gleason score7:

- A Gleason score of 6 or less indicates a low-grade or less aggressive cancer.

- A Gleason score of 7 is a medium-grade cancer

- A Gleason score of 8 or more is a high-grade cancer and more likely to grow and spread quickly.

The Gleason score and PSA levels are used together to determine the stage (extent) of the prostate cancer7:

- Stage I: Cancer is found in the prostate only. Gleason score 6 or less, PSA less than 10ng/ml.

- Stage II: Cancer is more advanced than in stage I, but has not spread outside the prostate. Gleason score 6-8, PSA less than 20ng/ml.

- Stage III: Cancer has spread to the seminal vesicles or to nearby tissue or organs, such as the rectum, bladder, or pelvic wall. This stage is also known as “locally advanced prostate cancer”.

- Stage IV: Cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones or distant lymph nodes. This stage is also called “advanced prostate cancer”.

Treatment of Prostate Cancer

Prostate Cancer Treatment Options

The indication for starting treatment for prostate cancer depends on many factors such as7:

- How fast your cancer is growing.

- The stage of the cancer (PSA level, Gleason score, how much of the prostate is affected by the cancer, and whether the cancer has spread to other places in the body).

- Your age, overall health and any other treatments you may have for other illnesses.

- The potential benefits and side effects of treatment.

- Your preferences.

- Whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has recurred (come back).

Treatment options for prostate cancer include4,5,7,9:

- Active surveillance: In some cases, because prostate cancer may take many years to progress, and treatment does have its risks, doctors may choose to simply monitor the tumour rather than treat it immediately. This is known as “active surveillance”. It may be an option in cases where the cancer is not causing symptoms, expected to grow very slowly and confined to a small area of the prostate. It may also be considered for someone who has other serious health issues or in frail, elderly patients who may not tolerate the treatments. In active surveillance, follow-up blood tests, rectal exams, prostate biopsies or scans may be performed at regular intervals to monitor your cancer closely. Treatment may be started if the tests show that your cancer is progressing.

- “Watchful waiting” is a reasonable option for certain men with prostate cancer, such as elderly men without symptoms who have a short life expectancy due to advanced age or the presence of multiple illnesses. Watchful waiting involves a less intensive follow-up schedule that involves less tests compared to active surveillance, with treatment considered only when symptoms occur.

- Surgery: Prostate cancers that have not spread beyond the prostate is commonly treated and possibly cured with surgery. A surgical procedure to remove the prostate, surrounding tissue, and seminal vesicles is known as radical prostatectomy.

- Radical prostatectomy may be performed as a laparoscopic procedure, in which the surgeon makes several small incisions (cuts) in the abdomen and passes long, thin surgical tools through the incisions to remove the prostate and nearby tissues. More commonly, the surgeon sits at a console or control panel to precisely move robotic arms that hold the tools (known as robot-assisted prostatectomy or robotic prostatectomy).

- Potential side effects from surgery include urinary incontinence (unable to control urine) and erectile dysfunction (difficulty with erections). If there is suspicion that the cancer might have spread to nearby lymph nodes, the surgeon may first remove some of these lymph nodes (known as a pelvic lymph node dissection). The nodes are sent to the laboratory and examined under microscope. If cancer cells are found in any of the nodes, the surgeon may not continue with the surgery as it would be unlikely for the cancer to be cured with surgery, and removing the prostate has risks of serious side effects10.

- Radiation therapy: Radiation therapy uses high-powered energy to kill cancer cells. Prostate cancer radiation therapy treatments may involve:

- External beam radiation (Radiation that comes from outside of your body): External radiotherapy uses a machine outside the body that delivers radiation towards the cancer. It can be used as first treatment for treating low risk cancers that are contained in the prostate. In such cases, the cure rate is similar as those treated with radical prostatectomy11. It is also an option after surgery to kill any potential remaining cancer cells. For prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones, radiation therapy can help to slow the cancer's growth and relieve symptoms such as pain.

- Brachytherapy (Radiation placed inside your body): Brachytherapy involves placing radioactive substances contained in rice-sized radioactive seeds in your prostate tissue to release a low dose of radiation over a long period of time. It is an option for treating cancer that hasn't spread beyond the prostate.

- Proton beam radiation: Proton beam radiation therapy is a new form of high-energy, external radiation therapy that uses streams of protons (tiny particles with a positive charge) instead of x-rays to kill cancer cells. Protons cause little damage to tissues that they pass through and release their energy mainly at the target area. This means that proton beam radiation can deliver more radiation to the cancer with lower dose radiation and less damage to nearby healthy tissues.

Focal therapy: Focal therapy is a newer form of treatment aimed only at the area of the prostate containing the tumour, unlike surgery and most forms of radiation therapy, which affect the whole prostate:

- Cryoablation or cryotherapy for prostate cancer involves freezing the prostate tissue with very cold gas and thawing, in repeated cycles. The cycles of freezing and thawing kill the cancer cells and some surrounding healthy tissue.

- High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) treatment uses concentrated ultrasound energy to heat and destroy prostate tissue.

- Focal laser ablation uses intense heat directed at the tumour to destroy cancer cells in the prostate.

Many of these treatments are still considered experimental and may be an option for cancer that is confined to the prostate. These types of treatments are potentially less likely to cause side effects such as incontinence and erection problems12.

Hormonal therapy: Prostate cancer cells rely on testosterone to help them grow. Hormonal therapy (also known as androgen deprivation therapy) counters the effects of testosterone which may cause cancer cells to die or to grow more slowly. It may be used following surgery or radiation therapy to treat advanced prostate cancers that have spread beyond the prostate gland and cancers with high-risk features. Hormone therapy alone does not cure prostate cancer, and many cancers may develop resistance to hormone therapy over time13. Hormonal therapy options include:

- Medications that stop testosterone production: Certain medications (known as luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) or gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists) lower the amount of testosterone made by the testicles.

- Medications that block testosterone from reaching cancer cells: These medications (known as anti-androgens) are often given in conjunction with LHRH agonists.

- Surgery to remove the testicles: Removing your testicles (known as orchiectomy) depletes testosterone levels in your body quickly and significantly. However, unlike medication options, this option is permanent and irreversible.

- Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy is the use of anti-cancer drugs to destroy cancer cells or stop them from dividing. It does not cure the cancer, but it can help to control symptoms by shrinking the cancer and slowing its progression. Chemotherapy is generally given to patients with advanced prostate cancer when they are no longer responsive to hormonal treatment.

- Immunotherapy: Immunotherapy is treatment that boosts the patient’s immune system to fight the cancer. This can be done by genetically engineering your own immune cells to fight prostate cancer cells, or using medications that help your immune system cells identify and attack the cancer cells. Immunotherapy is an option for treating advanced prostate cancer that is no longer responding to hormonal therapy.

- Targeted drug therapy: Targeted therapies are drugs that block the growth of cancer by interfering with specific molecules present in cancer cells that are involved in tumour expansion and spread. Some targeted therapies only work in people whose cancer cells have certain genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2. It is usually used in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer that is no longer responsive to hormonal therapy or cancer that has returned after treatment.

If you are feeling overwhelmed by the vast number of treatments available, you are not alone. Many men in a similar situation find it very stressful to have to decide between treatment options, and often worry that they may choose the “wrong” one. But rest assured, most times there is no single option that is clearly better than the others. Furthermore, unless the cancer is known to be progressing quickly or has other worrying features, it is unlikely to require urgent treatment, so you can take your time to weigh up your options carefully with your treating doctor and family before deciding which one is right for you.12

Prostate Cancer Survival Rate

The following factors influence the outcome of prostate cancer patients1:

- Stage (extent) of the cancer.

- Gleason grade.

- Patient's age and health.

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level.

The overall survival rate for prostate cancer in Singapore has increased from 47% to 89% over the past fifty years2. The outcome for most men with prostate cancer is good, with a greater than 98% 5-year survival if diagnosed in Stages 1-314. This means that more than 98 out of 100 men with prostate cancer are alive five years after their diagnosis.

About 30% of patients are diagnosed with advanced (Stage IV) prostate cancer and the prognosis for this group is less favourable, with a survival rate of 49%14. It is worth noting that survival rate statistics are measured every 5 years and therefore may not reflect the recent advances in prostate cancer treatment. People who are diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer now are likely to have a better prognosis (outcome) than these numbers show. Furthermore, breakthroughs in cancer research are happening at a faster pace than ever before, providing greater insights and leading to the development of more effective treatment options to improve the outcome and quality of life for those diagnosed with prostate cancer. If you have advanced prostate cancer, you may wish to speak to your treating doctor to find out if there are clinical trials suited to your individual situation.

Prevention & Screening for Prostate Cancer

Prostate Cancer Screening

Screening refers to looking for cancer before a person has any symptoms. Screening can help doctors find and treat prostate cancer early, when the cancer is localised and more easily removed by surgery. At present, there is a lack of evidence to support routine screening for prostate cancer for the general population in Singapore.

One of the tests used for prostate cancer screening is the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test, which measures the level of PSA (a protein produced by the cells in the prostate gland) in the blood. The higher the level, the more likely cancer is present, although other conditions, such as prostate infection, inflammation or enlargement, may cause an elevated PSA reading as well. The PSA test is not a highly accurate test and can sometimes show abnormal results even when a man does not have cancer (known as a false-positive result), or normal results even when a man does have cancer (known as a false-negative result). False-positive results can result in some men undergoing unnecessary prostate biopsies (and the small risks of pain, infection, and bleeding). On the other hand, false-negative results can give some men a false sense of security that they do not have cancer, and miss the opportunity to treat the cancer early.15

Given the complexities, it is recommended that you have a discussion with your treating doctor who will be able to provide you with information tailored to your situation and help you in making an informed decision about screening for prostate cancer. This discussion should take place around the age of 50 for most men at average risk for prostate cancer, and age 40-45 for men at high risk16 (see Prostate Cancer Risk Factors above). Screening is usually done with a PSA blood test and a digital rectal examination (DRE) where the doctor inserts a gloved and lubricated finger into the rectum to feel for any abnormalities in the prostate.

Prostate Cancer Prevention

While there is no guaranteed way to prevent prostate cancer, there are some measures you can take to reduce your risk4:

- Maintain a healthy body weight: A healthy diet and regular exercise can help you to keep to a healthy body weight and reduce your risk for many conditions including prostate cancer.

- Eat a healthy, balanced diet: A diet with less fat, sugar, red meat and highly-processed foods, and more fresh fruits, vegetables and whole grains can help to reduce the risk of many diseases and cancers including prostate cancer.

- Choose healthy foods over supplements: So far studies have not shown conclusive evidence that support the role of supplements in reducing prostate cancer risk. Instead, opt for foods that are rich in vitamins and minerals to maintain healthy levels of vitamins in your body.

- Stay active and exercise regularly: Exercise improves your overall health and wellbeing. Try to exercise most days of the week. If you are new to exercise, start slow with a gentle activity such as a walk around the park, and work your way up gradually.

- Go for regular screening if you are in the high-risk group (see Prostate Cancer Risk Factors above).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Most prostate cancers are not caused by inherited cancer genes, but rather by spontaneous DNA mutations (changes) acquired during a person’s lifetime. Inherited syndromes only account for around 10% of prostate cancers17.

Inherited mutations in specific genes that are linked to hereditary prostate cancer, include17:

- BRCA1 and BRCA2: Inherited mutations in either of these genes are linked to an increased risk of prostate cancer in men and also a greatly increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer in women.

- CHEK2, ATM, PALB2, and RAD51: Mutations in these genes might also be responsible for some hereditary prostate cancers.

- DNA mismatch repair genes (such as MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2): Men with inherited mutations in these genes have a condition known as Lynch syndrome (also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC), and are at increased risk of colorectal, stomach, prostate, and some other cancers.

- HOXB13: Mutations in this gene are associated with early-onset prostate cancer that runs in some families.

If you have prostate cancer, testing the cancer cells for these gene changes might be important for17:

- Guiding treatment choice: The results of genetic testing might affect your treatment options. Some drugs, such as certain targeted drugs are only likely to work if your cancer cells have a specific mutation.

- Further genetic counselling and testing: If the cancer cells have a gene mutation, testing some of your healthy cells (such as from a blood sample) for the same mutation can show if you inherited it, in which case the mutation would be found in all your cells and not just your cancer cells. This might help you learn more about your risk of other cancers, as well as your family members’ risks. Your doctor may refer you to a family genetic counselling specialist if required.

All treatments for prostate cancer can potentially lead to infertility18:

- During a radical prostatectomy, the surgeon cuts the vas deferens, which are the pathways between the testicles (where sperm are made) and the urethra (through which sperm leave the body). Your testicles will still make sperm, but they are unable to leave the body as part of the ejaculate. This means that you will not be able to father a child the natural way.

- After radiotherapy, chemotherapy or hormone therapy for prostate cancer, you might produce less or no semen. These treatments might also damage sperm and reduce your sperm count, making it more difficult for you to have children naturally.

- However, it is still possible for some men to be fertile during their treatment with radiotherapy, hormone therapy or chemotherapy but the sperm may be damaged. For this reason, it is important that you find out from your doctor how long you should wait after treatment to resume unprotected sexual activity or to try for a pregnancy.

- You may wish to consider storing sperm before starting treatment if you plan to have children in the future. Speak to your doctor about a referral to a specialist fertility clinic.

Prostate cancer often does not show symptoms until it is advanced. Signs to look out for include19:

- Difficulty urinating including difficulty starting and stopping, weak flow and frequent urination especially at night

- Pain or a burning sensation during urination or ejaculation

- Pain around the prostate whilst sitting

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Sudden erectile dysfunction

Prostate cancer has one of the best treatment outcomes among all cancers. With early diagnosis and treatment, it is often curable. Most men with prostate cancer are likely to die of other ailments related to old age rather the cancer itself.

References

- National Cancer Institute. Prostate Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. Accessed at https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/hp/prostate-treatment-pdq on 24 June 2024.

- National Registry of Diseases Office. Singapore Cancer Registry Annual Report 2021. Singapore, National Registry of Diseases Office; 2022.

- Chin H. et al. Prostate Cancer in Seniors. Federal Practitioner. 2015 May; 32(Suppl 4): 41S–44S.

- Mayo Clinic. Prostate Cancer. Accessed at https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prostate-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20353087 on 24 June 2024.

- Cleveland Clinic. Prostate Cancer. Accessed at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/8634-prostate-cancer on 24 June 2024.

- American Cancer Society. Prostate Cancer Risk Factors. Accessed at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html on 24 June 2024.

- National Cancer Institute. Prostate Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version. Accessed at

- https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq on 24 June 2024

- American Cancer Society. Tests to Diagnose and Stage Prostate Cancer. Accessed at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/how-diagnosed.html on 24 June 2024.

- Singapore Cancer Society. Prostate Cancer. Accessed at https://www.singaporecancersociety.org.sg/learn-about-cancer/types-of-cancer/prostate-cancer.html#risk-factors on 24 June 2024.

- American Cancer Society. Surgery for Prostate Cancer. Accessed at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/treating/surgery.html on 24 June 2024.

- American Cancer Society. Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Accessed at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/treating/radiation-therapy.html on 24 June 2024.

- American Cancer Society. Considering Treatment Options for Early Prostate Cancer. Accessed at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/treating/considering-options.html on 24 June 2024.

- American Cancer Society. Hormone Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Accessed at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/treating/hormone-therapy.html on 24 June 2024.

- National Registry of Diseases Office. Singapore Cancer Registry 50th Anniversary Monograph – Appendices. Singapore, National Registry of Diseases Office; 2022.

- American Cancer Society. Can Prostate Cancer be Found Early? Accessed at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/detection.html on 24 June 2024.

- American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Early Detection. Accessed at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html on 24 June 2024.

- American Cancer Society. What Causes Prostate Cancer? Accessed at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/what-causes.html on 24 June 2024.

- Cancer Research UK. Infertility After Prostate Cancer Treatment. Accessed at https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/prostate-cancer/practical-emotional-support/sex-relationships/infertility-prostate-cancer-treatment on 24 June 2024.

- Moffitt Cancer Center. What are the Five Symptoms of Prostate Cancer? Accessed at https://www.moffitt.org/cancers/prostate-cancer/faqs/what-are-the-five-warning-signs-of-prostate-cancer/ on 24 June 2024.